The report provides examples of how enrichment can reach some of the most marginalised children with poor school attendance, some of whom are less likely to respond to other methods of engagement. While the evidence-base on links between education and enrichment needs further investment, the report’s case studies show the correlations between enrichment and attendance, with children and young people with higher attendance telling our researchers they are more likely to be attending school because of enrichment activities.

The research was commissioned by NCS Trust and the DofE and highlights the potential of enrichment activities to boost student engagement and improve attendance. It was conducted in response to the growing concern about school absenteeism, which has risen dramatically in recent years.

We are deeply grateful to our colleagues and friends in the fields of economics and children and young people’s mental health, who generously shared their research, insights, and advice to help inform this report.

In particular, we would like to thank Professor Peter Fonagy (University College London), Professor Praveetha Patalay (University College London), Professor Mark Mon-Williams (University of Leeds), Professor Sir Julian Le Grand (London School of Economics), Professor Cathy Creswell (University of Oxford), Professor Pat McGorry (University of Melbourne), Dr Tessa Crilly and Pro Bono Economics.

Please note that their involvement does not imply endorsement of the report’s specific details or recommendations.

The decline in young people’s mental health is one of the biggest health, social and economic challenges of our time. After a sharp rise in recent years, more than one in five children and young people in England now have a diagnosable mental health condition. Despite this, the NHS is only able to support around 40% of those in need and fewer still are getting the right care for them. Mental health services are unable to keep up, and millions are suffering.

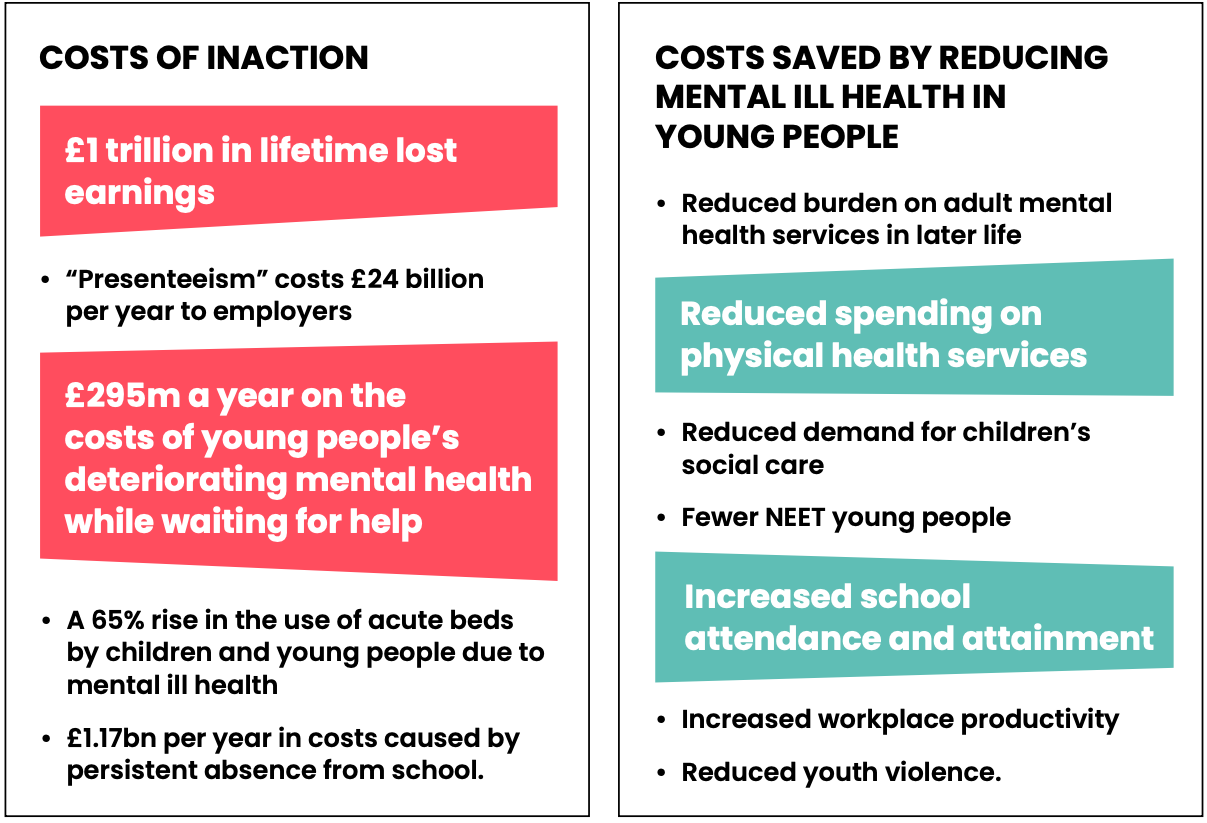

As well as the huge human cost, this crisis has major implications for the public purse and wider economy. Failing to adequately address it creates far costlier outcomes across a range of public services, including in health, education, welfare, policing and justice. It harms productivity, earnings and the Government’s agenda for economic growth. On top of this, due to the long-term impacts of poor mental health, we have yet to feel the full effects of the recent rise in prevalence. Current trends are simply not sustainable.

The Government’s agenda for public service reform and economic growth provides the perfect platform to take the necessary action for young people. Taking steps to turn around the youth mental health crisis will help the Government progress four of its five Missions: Growth, Opportunity, Health, and Safer Streets.

We recommend immediate and scalable steps the Government can take to close the treatment gap and provide earlier support that prevents problems from escalating.

We also propose a Government-commissioned review that would authoritatively identify root causes of the crisis – examining the role of, for example, inequalities, the pandemic and social media – and the failings of the mental health system itself. Finally, we outline measures that could be delivered through local government and make a real difference in the long-term prevention of mental ill health in young people.

We acknowledge that we are calling for additional funding at a time when public finances are strained. However, as our analysis makes clear, the immediate and longterm costs of inaction are far greater than the investment we are calling for.

Spending on incapacity and disability benefits for working age people is forecast to increase by £29 billion by the end of this Parliament, driven in large part by the rising number of young people with mental health problems. Our analysis shows that the impact of childhood mental health problems leads to £1 trillion in lost earnings across the generation. We also find that the costs of persistent absence from school – which has mirrored the rise in mental ill health – are now over £1 billion per year.

This crisis also has huge costs to the health system. The lack of capacity in the system means far too many young people reach crisis point, putting pressure on emergency, urgent and crisis services, straining bed capacity, and creating enormous waiting times.

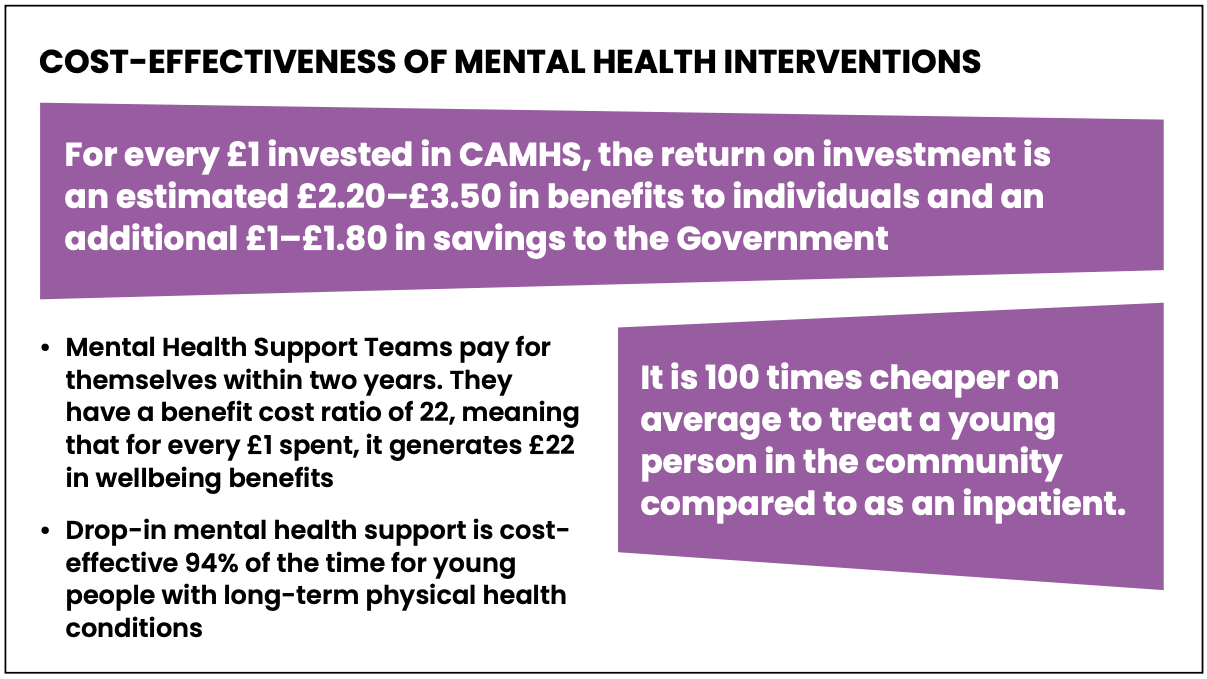

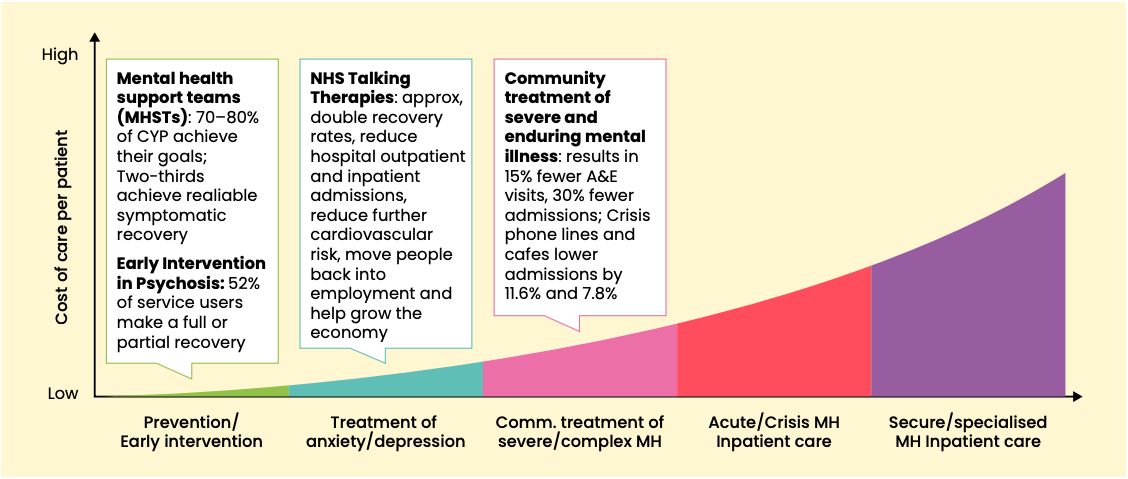

We find that the cost of deteriorating mental health between referral and receiving support is now £295m a year. There has been a 65% rise in the use of acute beds by children and young people due to mental ill health. These are often inappropriate sites of care, as well as reducing the capacity of physical healthcare services. It is 100 times cheaper to treat a young person in the community than as an inpatient. However, we cannot benefit from these efficiency savings without building capacity in the system first. That requires upfront investment.

We are calling for proven cost-effective interventions. For example, for every £1 invested in child and adolescent mental health services, the return on investment is an estimated £2.85 in benefits to individuals and an additional £1.40 in savings to the Government. These savings could be made greater by increasing capacity, broadening the workforce and shifting more care into community settings. In addition, Mental Health Support Teams in schools pay for themselves within two years.

Investing in children’s mental health is not only a moral imperative but also an economic necessity. The current crisis is a ticking time bomb – we risk losing a generation. By addressing this challenge now, the Government has an opportunity to secure a healthier, more prosperous future for young people and wider society. The evidence is undeniable: investing in high-quality prevention, early intervention, and accessible services can reverse current trends, reduce long-term costs, and unlock the potential of an entire generation.

One in five children and young people experience a common mental health problem, such as anxiety or depression (NHS Digital, 2023). This is almost double the 2017 figure. Millions of families across the country are experiencing the everyday reality of a young person living in distress or requiring care to manage a mental health problem. We are in the middle of a crisis that has huge implications for the future of our young people, our health service and our economy.

This is not a cultural phenomenon, as some have claimed, but a real and significant increase in rates of distress and diagnosable illness – and an escalating public health crisis. Yet for too long, even as these numbers escalated, policymakers failed to fully grasp the potential of doing more to support the mental health of young people. The possibility of a future where fewer young people end up in hospital, missing school or unable to work due to their mental health. A happier, healthier, more productive future.

The good news is that change is within reach. Within the core Government priorities to reform public services and drive economic growth, there is a huge opportunity to prioritise children and young people’s mental health – and to reverse these worrying trends. And, both in the UK and internationally, there are proven cost-effective models of care that, if delivered at scale, could have a transformative effect on young people’s health and our economy (McGorry et al., 2024).

We are therefore proposing a bold and ambitious plan for reform and investment that could quickly reap economic, health and social rewards.

1. Increased investment in children and young people’s mental health services, with a commitment to meeting 70% of diagnosable need by the end of this Parliament.

Current spending on children and young people’s mental health amounts to just over £1.1 billion per year, meeting only 40% of need. To meet 70% of need by the end of this parliament, an additional £167 million will be needed in the first year, with further incremental increases required by the end of the 2028/29 financial year (see below).

2. The full rollout of Mental Health Support Teams by the end of this Parliament, with a commitment to adapt the model to meet a broader range of need.

Commit to £455 million per year by 2028/29 to enable 100% of national coverage for Mental Health Support Teams – this money should be part of an overall increase in spending on children and young people’s mental health services, per the previous ask

3. The delivery of open access mental health services for children and young people in every community, initially through the Young Futures programme.

Allocate £169 million per year to roll out a national network of open access mental health hubs for children and young people up to age 25 in every local authority area. A further £74m to £121m should be identified to cover capital and set up costs.

4. A comprehensive children and young people’s mental health workforce plan.

Not costed; however, this would quantify the human resources that underpin the costings outlined above.

5. An independent Government-commissioned rapid review to examine the causes of the rise in prevalence in children and young people’s mental health, and the ways in which our mental health system can respond better.

Not costed

6. Increased local government funding to support investment in prevention and early intervention.

Return the public health grant and youth services spending to at least 2015/16 level, £750m and £1.4 billion per year respectively, and address the gap in spending for children’s services and provision for Special Educational Needs and Disabilities. For children’s social care, a minimum investment of £3 billion will be needed to address the shortfall in spend.

The costings set out in this briefing are based upon existing data and economic analyses which we have used to generate updated estimates with the latest figures available. The topics outlined above are examined in greater depth in the sections below.

"Mental health struggles have had a huge impact on my life, making it very difficult to live life at points. I started struggling when I was 13.

I have OCD, so this looked like hand washing, but also confessional OCD. I spent a lot of time feeling guilty, and I used to compulsively apologise. This made me stand out, which led to bullying from people at school. This turned into a vicious cycle. My mental health struggles led to me getting picked on, which led to a worsening of my mental health. During Covid-19 this worsened, and I became isolated. I did not want to touch handles, so would often feel stranded around school waiting for someone to open the door. My OCD was constantly triggered whilst at school during Covid, which often became too much, so I had lots of days off. This further increased my anxiety as I missed school.

I first reached out for support when I was 13. My mum took me to see a counsellor. This was hard at the time. I didn’t know what a counsellor was, and I barely knew what mental health was. This made it very tricky and very nerve-wracking. I thought I was strange and weird because I needed extra help with my thoughts. However, seeking support was the best thing I have ever done. I can truly say I don’t think I would be here today if it was not for my counsellor. My counsellor has helped me work through my struggles and given me techniques to deal with them. I also received support from teachers at school. One teacher in particular helped me out a lot. She always allowed me to use her room when I needed a break, and was always there for me when I needed her. She also stood up for me when I didn’t feel like I had my own voice. The support of my counsellor and some teachers really enabled me to turn my life around.

I now spend much of my time campaigning around the issue of mental health. Before I started campaigning, I used to spiral into low self-esteem and dislike of myself, because of what I put me and my family through. However, I now use these negative experiences to try and help other people who may find themselves in similar situations.

Mental health campaigning is my favourite thing to do, and I feel like I am living my best life now! This has only been possible because I reached out for support, and the support has been so effective."

Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS) is an umbrella term that encompasses the services and support available to promote and address the mental health needs of babies, children, and young people, aged 0 to 25.

This includes support provided under the more familiar term CAMHS (Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services), as well as a broader range of statutory and non-statutory provision. CYPMHS offers support across the spectrum of mental health needs, from prevention and early intervention to urgent and crisis care. A wide range of organisations contribute to these services, ensuring comprehensive support that meets the diverse needs of children and young people. Key actors in England include:

Together, these services form a network of support designed to address the mental health needs faced by babies, children and young people, ensuring that help is available at every stage and level of need.

All youth mental health support is a form of early intervention, helping to address issues before they escalate. This not only reduces future demands on mental health and welfare systems but also decreases associated costs across education, physical health services, and social care. Unlike physical health problems, which are generally more likely to occur as people get older, three-quarters of mental health problems are established by the age of 24 (Kessler et al., 2005). There is strong evidence that youth mental health is one of the most cost-effective areas of intervention in all healthcare (Mental Health Australia & KPMG, 2018), bringing a range of lasting economic and health benefits in later life (Cardoso & McHayle, 2024).

Poor mental health is estimated to cost the economy at least £300 billion a year in England (Cardoso & McHayle, 2024) and the Government has clearly identified how rising prevalence of mental ill health in young people is having a huge impact on labour market participation (HM Government, 2024). This harms economic growth, reduces tax receipts and sharply impacts Government spending on benefits (Murphy, 2024).

There is a well-established “scarring effect”, where health and employment problems experienced in early adulthood are repeated across the life course (McCurdy & Murphy, 2024). Mental health can be a critical causal factor in this – a major study published in 2015, analysing 50 years of child development data, estimated that the long-term impact of mental health problems in childhood costs the UK a total of £550 billion in lost earnings across the lifespan (UCL, IFS & RAND Corporation, 2015). This is likely to be an underestimate of current lost earnings, and lower than the potential lost earnings faced by the current cohort of children and young people given the rising rates of mental health difficulties according to more recent figures.

Analysis also revealed that this financial impact grows significantly with age – those who experienced childhood mental health problems earned 20% less than their peers by age 23, 24% less by age 33, and 30% less by age 50. This emphasises the enduring impact of failing to intervene early.

Since the study was conducted, the prevalence of poor mental health among children and young people has nearly doubled. Adjusting for the increase in the number of UK households and the rise in prevalence, our estimates put today’s losses at a total of over £1 trillion – before adjusting for inflation.

Alongside lost wages, poor mental health has huge implications for productivity. A survey conducted by Deloitte in 2024 found that “presenteeism” – where people are working while unwell – costs UK employers £24 billion per year (Deloitte, 2024). The same survey also identified the indirect impacts of poor mental health on employers, with 46% of working parents saying they are concerned about their children’s mental health. This costs UK employers £8bn annually due to reduced performance, time missed for caring responsibilities, or parents leaving their roles entirely.

As young people continue to enter the labour market, cost-benefit approaches to addressing mental health needs must consider potential future economic losses, as well as those already being felt.

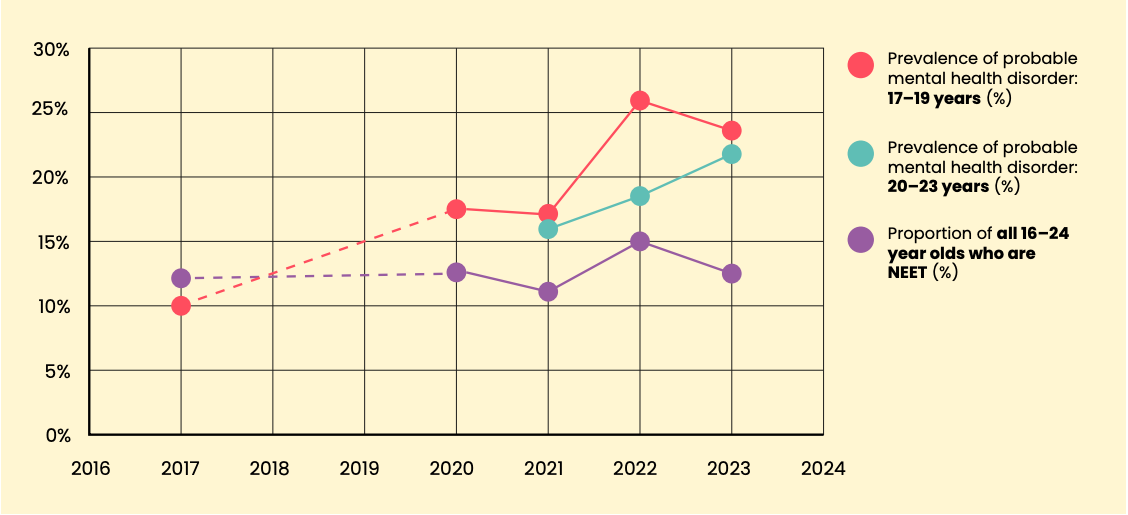

Spending on working-age incapacity and disability benefits is forecast to rise by £21 billion per year in real terms by 2028-29 (Judge & Murphy, 2024), with mental ill health driving claims among young adults – the number of young people who are unemployed due to ill health more than doubled from 93,000 in 2013 to 190,000 in 2023 (McCurdy & Murphy, 2024). The figure below places rates of diagnosable mental health difficulties among young people alongside the proportion of 16-24 year olds out of employment, education or training in the period between 2017 and 2023 and shows a clear, measurable correlation in England.

The revived Mental Health of Children and Young People in England survey was conducted in 2017 but its second wave was not held until 2020, accounting for the gap connected by the two dotted lines in the below figure. Similarly, 20-23 year olds were only included in the survey from 2021 onwards.

Economists at the Resolution Foundation have looked more deeply into the relationshipbetween rising rates of mental ill health and of young people who are NEET. Across 2018to 2022, 21% of 18-24 year olds with a common mental health disorder were neither ineducation nor employment, compared to 13% of those without (McCurdy & Murphy,2024). Without action, we face the harsh economic consequences of ever-greaternumbers of people in long-term unemployment and far greater pressure on our welfaresystem.

School absence rates rose sharply during the pandemic and, while the worst impacts of Covid-19 faded away, absence rates have remained stubbornly high (Long & Roberts, 2025). In 2022/23, over a fifth of pupils were recorded as persistently absent (missing 10% or more of school sessions) in England – double the rate in 2018/19. This trend remains a persistent concern for experts across education, health and social care sectors, with absence rates remaining above 7% compared to pre-pandemic levels of under 5%. School absence, alongside its links to attainment, is a well-established precursor of a range of economic and social challenges, with major implications for the future of our workforce and economy (Sibieta, 2021).

NHS Digital data demonstrates a strong relationship between mental ill health and school absence (NHS Digital, 2023). In 2023, 11.2% of pupils aged 8-16 in England with probable mental health disorders missed more than 15 days of school in a term, compared to only 1.5% of pupils without (Ibid). Further data shows that 61% of surveyed young people aged 16-24 who are waiting for mental health support stop attending school or college (M&S and YoungMinds, 2023). This highlights the immediate cost of limited capacity in children and young people’s mental health services.

The cumulative costs of persistent school absence are substantial. An Early Intervention Foundation (2018) analysis estimated that the cumulative annual costs of persistent absenteeism were £484 million in 2016, felt predominantly in the education, health and justice systems. Persistent absence has risen by 79% since 2016. Accounting for this and inflation, it can be estimated that the cumulative costs of persistent absence were £1.17 billion in the 2023/24 school year.

With 75% of mental health problems presenting before the age of 24, failing to appropriately support a young person increases the likelihood of someone needing formal mental health support as an adult, with major long-term cost implications. There is also a strong association between mental health difficulties and having multiple physical health conditions, as well as reduced life expectancy (Rizzol et al., 2023). This too has significant long-term cost implications for NHS resourcing, as well as benefits spending. However, it can be mitigated by targeted support – a recent study found drop-in mental health support pays for itself for 94% of young people with long-term physical health conditions (Clarke et al., 2022).

The long-term failure to adequately resource children and young people’s mental health services has led to demand continuing to far outstrip supply, even as services have increased their capacity. Notoriously long wait times for support have a major effect on other services, such as A&E, urgent and crisis care, and acute wards. Recent analysis of data on admissions to acute medical wards for mental health concerns among children and young people in England revealed a 65% increase in annual admissions between 2012 and 2022 (Ward et al., 2025). These are not only often inappropriate settings for young people in mental health crisis, but this also has a substantial impact on hospital capacity.

In addition, there is an immediate financial impact of the wait times themselves, particularly on education settings, as well as social services and non-CAMHS. By applying 2022/23 data to methodology established by Pro Bono Economics (2020b), we estimate the annual costs of waiting for care for young people is £295 million, having risen from £75m in 2018/19. This almost 300% rise owes to significant increases in both referrals and average waiting times.

Some groups of children and young people face a disproportionate burden of mental health challenges, primarily due to complex social and environmental factors. For instance, children in poverty are four times more likely to experience severe mental health difficulties by age 11 compared to their wealthier peers (Gutman et al., 2015). Autistic young people, those with physical or learning disabilities, and individuals from racialised or LGBT+ communities also report significantly higher levels of mental health difficulties (Rainer and Abdinasir, 2023).

Failing to address these inequalities perpetuates a vicious cycle where poor mental health reinforces disparities across lifetimes and generations. This compounds harm and increases societal costs, underscoring the need to tackle inequalities at their root.Additionally, tackling inequitable access to mental health care must be a priority as services expand to ensure no one is left behind.

The implications for our economy and public services of failing to tackle this crisis are undoubtedly severe. However, there is clear evidence that mental health interventions can have a transformative effect on young people’s lives, reducing or eliminating the effects of mental ill health – and unlocking their potential.

The recent global Lancet Commission on youth mental health shows how other governments have recognised and are actively addressing this pressing challenge through reform and investment (McGorry et al., 2024). Drawing on this and the wider evidence base, we aim to outline how the Government can seize the opportunity that comes with this moment of health reform and take decisions in the Spending Review that turn the tide on this crisis and support economic growth.

Despite the enormous and growing cost of mental ill health in young people – and the clear benefits of early intervention – children and young people’s mental health services continue to be considerably under-funded relative to demand (Garratt et al., 2024), exacerbating the legacy of the historical underspend on mental health services (Mental Health Foundation, nd).

The Government’s 10 Year Plan for Health is a unique opportunity to transform services and reduce pressure on urgent and emergency services by improving early intervention support. However, achieving the Government’s desired shifts towards prevention, community care and digital improvement in children and young people’s mental health requires significant investment – to rectify historical under-resourcing and to build capacity across the range of systems that support young people’s mental health.

The Darzi Review highlighted that mental health only receives 10% of NHS spending, despite accounting for 20% of the UK’s morbidity burden. Within that, children and young people’s services receive only 8% of overall mental health spending (Garratt et al., 2024), despite government figures showing that under-18s account for 31% of people in contact with mental health services annually (UK Parliament, 2024).

While there is immense pressure on NHS budgets across all conditions and services, it is impossible to accept the gap between provision and need in children and young people’s mental health – particularly when there is considerable evidence about the cost-effectiveness of Government-funded mental health interventions (Frayman et al., 2024), with the health and economic benefits especially pronounced (Mental Health Australia & KPMG, 2018).

For example, analysis by Pro Bono Economics (2020a) shows that treatments provided by NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services provide projected savings of between £1.7 and £2.7 billion in long-term societal benefits to individuals, and total longterm savings to government of between £0.9 and £1.4 billion in England. On a per-person basis, this equates to approximately £4,400 to £7,000 in private benefits and £2,300 to £3,700 in government savings for each young person treated. Furthermore, the report concludes that for every £1 invested in CAMHS, an estimated £2.20-£3.50 in benefits to individuals and £1.00-£1.80 in savings to the Government could be realised, highlighting the significant value of early mental health intervention. All figures have been adjusted by the authors of this briefing for inflation.

One major impact of the treatment gap is a huge challenge with waiting times. Despite NHS England’s stated commitment to a 28-day waiting time target, children and young people in England were found to waiting 21 weeks on average for a first appointment with CAMHS, as revealed by FOIs in April 2023. 40% of Trusts have a young person who has waited over two years. And the escalation of mental health challenges while waiting for support has significant health, social and economic impacts on young people, their families and the systems around them (Pro Bono Economics, 2020b).

The Government’s agenda for NHS reform is timely, as there are huge potential gains in efficiency and clinical outcomes in children and young people’s mental health care. As illustrated in the image below, it is 100 times cheaper (Northover, 2021) to treat a young person in the community compared to an inpatient setting, and the Government’s commitment to shift from hospital to community care presents a major opportunity to seize on these savings. However, change in these systems will be impossible without upfront investment that a) redresses the historical shortfalls in funding for services and b) significantly scales up community mental health infrastructure and workforce capacity. These changes are also critical in enabling the Government to deliver on the promises of a reformed Mental Health Act.

Figure 2: Cost of care per patient

The NHS Digital survey on children and young people’s mental health provides the latest data on the prevalence of diagnosable mental health conditions in 8-25 year olds in England. The first survey of this kind was completed in 2004, and it was well over decade before the next survey was conducted in 2017. This delay meant that services were often designed based on outdated data from 2004, contributing to the historic underfunding of children and young people’s mental health services.

After regular surveys on the prevalence of need since 2017, we are concerned that this programme was discontinued in 2023 with no current plans for its renewal. Given the significant rise in need over recent years, we cannot afford to have another data vacuum. It is crucial that funding and commissioning decisions are data-driven, but without this survey in place, there will be a far poorer understanding of wider population need.

In England, efforts over the past decade have focused on transitioning to a 0-25 model of care, aiming to prevent the “cliff edge” in support that many young people face between the ages of 16 and 25. This shift also prioritises more community-based provision. However, the reality for this age group remains starkly different. The European MILESTONE study revealed that only 19.6% of participants transitioned to adult services after reaching the upper age limit of child and adolescent mental health services (McGorry et al., 2024).

The NHS Long-Term plan, published in 2019, set an ambition that by 2030, 100% of children and young people who need specialist mental health support should be able to access it (NHS England, 2019). Whilst we fully support the ambition of this target, the Government has not provided a roadmap for how this can be achieved.

Currently, most children and young people with diagnosable mental health conditions are not receiving support from NHS Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS), highlighting a significant unmet need. To bridge this gap, expanding services is essential, and doing so will require increased investment across the full range of NHS-funded settings.

If, according to the most recent data, 39.6% of children and young people with diagnosable need have access to treatment or care, and £1.2 billion could be expected as planned spend for 2025/26 to achieve this, to work towards the target of reaching 70% of those with diagnosable need might be expected to cost an additional £167 million in the first year (Children’s Commissioner, 2024a). The table below shows how an incremental approach to increased spending until the end of this Parliament would unfold into rising additional funds. These figures would have to be increased to reflect inflation as years progress.

Table 1: Proposed phased rises to annual planned spend on children and young people’s mental health until 2028/29

Percentage

of need met

39.6%

45%

53%

61%

70%

Total spend required

£1.2 billion

£1.4 billion

£1.6 billion

£1.9 billion

£2.2 billion

Cumulative funding increase

N/A

+£167 million

+£415 million

+£663 million

+£942 million

The Mental Health Investment Standard (MHIS) is set by NHS England and sets out how much Integrated Care Boards (ICBs) should spend on mental health services each year. This plays an important role in addressing the historical underfunding of mental health. Whilst the MHIS should cover all mental health services, ICBs continue to allocate a drastically smaller percentage of their mental health budget to children and young people. This cannot continue. We need to re-balance the system so that children and young people’s mental health services receive an increased and equitable share of mental health funding.

The total planned spend in line with the Mental Health Investment Standard (MHIS) for 2024/25 is £11.79 billion (NHS England, nd). A planned ICB spend of £1.1 billion on children and young people’s mental health was reported for 2024/25 via the NHS Mental Health Dashboard (ibid). Between 2021/22 and 2024/25, the planned spend for mental health overall saw average annual rises of 7.5%; an increase at this rate for spending on children and young people’s mental health could mean an expected 2025/26 planned spend of £1.2 billion.

The cost of different treatments and services, as well as the severity of need, will shape calculations around the appropriate distribution of mental health spending between adults and children and young people. But a strengthened MHIS for children and young people should mirror the overall MHIS to ensure that, at a minimum, spending on CYPMHS increases by an equal or greater proportion to the overall increase in budget allocation each year. This will be an important tool to ensuring that national-level commitments on children and young people’s mental health are delivered at a local

level.

The Mental Health Support Team (MHST) programme aims to increase the availability of early mental health support in education settings. MHSTs support the mental health needs of children and young people in primary, secondary and further education (ages 5 to 18) through providing an evidence-based approach to early intervention. The programme began in 2018, and approximately 500 teams are now in operation, covering 44% of students in schools and further education in England (Department for Education, 2024). The Government has set a target to reach 50% coverage by March 2025; however, there is currently no funding guaranteed to ensure the programme will continue its rollout beyond this point.

An early evaluation of MHSTs indicated a range of positive outcomes reported by education settings who took part in the programme. Improvement in children and young people’s understanding of mental health and wellbeing was widely reported, as were strengthened relationships between education settings, mental health services and other local partners (Ellins et al., 2023). Despite this, the evaluation highlighted that children and young people continue to fall through the gaps in support between the remit of MHSTs and specialist services. Some groups of children and young people are also underserved by MHSTs, including those with special educational needs or neurodiversity, those from some ‘ethnic minority communities’, and children with challenging family or social circumstances (ibid).

Further studies support MHSTs as a cost-effective intervention for early intervention and prevention in school settings, with the investment recouped within two years (Frayman et al., 2024). And according to the Government’s original business case for MHSTs, the average benefits per intervention were estimated at £1,300 in healthcare savings, £1,350 in increased earnings, £2,750 in reduced crime costs, and £200 in educational benefits – amounting to a total of £5,600 per intervention (based on 2018/19 prices) (Department of Health and Social Care, 2018).

As part of any recommitment to this programme, the Government should address the limitations of some MHSTs identified in the ongoing programme evaluation, to ensure any expansion meets current gaps in need and is integrated with existing provision, such as school counselling and nursing. MHSTs should also be given flexibility to adapt to local need in the schools where they are working, such as by offering additional training on SEND or cross-cultural therapeutic work (Ellins et al., 2024).

As of January 2024, DHSC predicted that 50% of pupils in schools and colleges in England would be covered by MHSTs by March 2025 and in this costing of Labour’s (at the time) opposition policy, it was also assumed that each MHST covers around 8,500 pupils (Department of Health and Social Care, 2018).

At that time, the 400 MHSTs in place were understood to cover 35% of pupils (3 million), meaning that, with 100% coverage, a total of approximately 1,143 MHSTs might be expected (UK Government, 2024). Alternative methods of calculation offer different figures, but a sensible estimate would be just over 1,000 MHSTs being needed to achieve 100% coverage.

Early evaluation of MHSTs within the Children and Young Peoples Mental Health Trailblazer programme reported that sites received basic funding of £360,000 per year for each MHST, but high-cost areas were assigned additional funds (Ellins et al., 2023). In 2025/26, funding an estimated 1,000 MHSTs on the ‘basic’ model would cost £456 million (adjusted for inflation from £360 million in 2019/20). All figures below are based on 2025/26 prices.

Table 2: Proposed phased rises in funding of Mental Health Support Teams to reach 100% coverage of school pupils by 2028/29

MHST coverage

50%

62.5%

75%

87.5%

100%

Total spend required

£228m*

£285m

£342m

£399m

£456m

Cumulative funding increase

N/A

+£57m

+£114m

+£171m

+£228m

* Figure for 2024/25 is not reported actual spend as this amount has not been published. This is an estimate of possible spend in 2024/25 based on assumptions detailed above, including that the target of 50% coverage by March 2025 has been met.

In contrast, failing to roll out MHSTs to all children and young people could risk incurring costs of £1.8 billion, while each MHST is estimated to provide a potential £2 million to the state in savings (Barnardo’s, 2022). MHSTs have been identified as a significantly cost-effective model, with cumulative savings outweighing costs within two years based on an average pupil being treated (Frayman et al., 2024).

Enhancing the MHST model to cater for a broader range of needs would mean additional costs – such as for recruiting counsellors or other practitioners trained to work with more complex mental health needs or in specific cultural contexts. However, within such a cost-effective model, these additional training and recruitment costs are much preferable to the damaging impact of failing to intervene early in the community.

We strongly welcomed the Government’s manifesto pledge to deliver open access mental health support in local communities – initially through its Young Futures programme. There is a growing body of evidence that this model of early mental health support is highly effective in providing holistic support, increasing access to care for young people under-represented in other services, and improving young people’s mental health outcomes.

For example, a UK study examining the role of hubs implementing the Youth, Information, Advice and Counselling Services (YIACS) model (which provides open-access support) found that for young people who reported improvements in stress or health due to the advice received, the savings in GP costs alone were estimated at £108,108 per 1,000 clients (Balmer & Pleasence, 2012). This equates to £108 per young person, which surpasses the average cost of providing the advice.

It is important to note that, while they are both offer important early intervention support for young people, hubs provide a very distinctive offer from the above outlined benefits of MHSTs. Whilst MHSTs provide support predominantly in school and college settings, hubs are community-based and reach a broader and more diverse group of young people. This includes young people who sit outside the education system, such as those aged 16-25. Through providing a holistic and integrated offer of support, hubs also seek to address the determinants that contribute to poor mental health and provide a wide range of support that often goes beyond the remit of MHSTs.

A 2021 report based on a survey of Youth Access members delivering YIACS in England revealed key insights into their impact. The study found that YIACS supported a significantly higher proportion of young women (65%) compared to NHS CYPMHS (52%) (Youth Access, 2021). Key strengths of YIACS included its accessibility, its capacity to support young people during the transition ages, and its ability to engage a higher proportion of young people from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds compared to NHS CYPMHS or school-based counselling (ibid).

Similar international models offer valuable insights and show promising outcomes. For example, the Jigsaw model in Ireland, which supports young people aged 12 to 25, has demonstrated that brief early interventions can effectively reduce levels of self-reported psychological distress (O’Keeffe et al., 2015). Additionally, an independent evaluation of the Headspace model in Australia revealed significant reductions in suicidal ideation and self-harm among young people who accessed the service (KPMG, 2022). The recent Lancet Psychiatry’s Commission on Youth Mental Health also sets out further evidence and support for this model across several other jurisdictions including the USA, Netherlands, Canada and Japan (Garratt et al., 2024).

In 2024, the Department of Health and Social Care announced that 24 open-access mental health hubs for children and young people would share nearly £8 million to provide early mental health support. These hubs offer evidence-based psychological therapies, specialist advice, and support for broader issues affecting mental health, such as sexual health, exam stress, employment, substance use, and financial concerns (DHSC, 2024). Additionally, the department commissioned an independent evaluation, led by the NIHR Policy Research Unit in Mental Health (MHPRU), to assess the effectiveness of early intervention models and help policymakers evaluate the outcomes of Early Support Hub programmes in serving a diverse range of young people (UCL, 2024). Any national rollout of this model should incorporate lessons learned from this programme and other similar models. It is also vital that these hubs are delivered in line with the commitments outlined in the Government’s manifesto.

Centre for Mental Health has collected bottom-up spending data from a sample of existing hubs, generating overall figures for set-up and running costs for an average hub. Adjusting these calculations for early support to match inflation results in an estimated figure of £1.1-£1.4 million in running costs per hub, meaning an annual total of approximately £169 to £210 million for 153 hubs.

Capital costs for the set-up of hubs could reach between £890,000 and £1.46 million per hub. Presuming that 70 existing hubs are still operational, the set-up costs of national roll-out would be between £74 million and £121 million (based on 153 local authorities excluding district councils). Some set-up costs could perhaps be offset if existing facilities or organisations could be adapted or scaled up into early support hubs.

Across healthcare settings, it’s clear that any expansion of capacity must be accompanied by a workforce plan. However, because of the historical failures to adequately resource or prioritise children and young people’s mental health, there has been a particular lack of long-term workforce planning in this space.

The 15-year horizon of the NHS Long Term Workforce Plan showed welcome recognition of the need to forward plan (NHS England, 2023), but the commitments on children and young people’s mental health were unambitious. Additionally, workforce strategies to date have largely overlooked the role of other key partners and professionals, including those working within councils, the voluntary and community sector, and including digital provision.

Ongoing workforce challenges were underscored in the 2023 Health Education England Children and Young People’s Mental Health Workforce Census, which highlighted significant issues with staff vacancies and retention in mental health services for children and young people. NHS staff vacancy rates rose from 9% in 2021 to 17% in 2022 (HEE, 2023). Staff retention also declined, with only 77% of staff remaining in post throughout the 2022 financial year, compared to 83% in 2019 and 80% in 2021 (ibid). The census further identifies gaps in workforce provision, including a shortage of specialist staff to support children and young people with eating disorders (ibid). Addressing these gaps will be essential for creating a truly comprehensive and sustainable workforce plan.

The introduction of roles such as Educational Mental Health Practitioners within Mental Health Support Teams and Children’s Wellbeing Practitioners, which offer salaried training pathways into the children and young people’s mental health workforce, has significantly contributed to workforce growth. Future workforce expansion plans should build on the success of these initiatives. While the Government’s commitment to further expand the mental health workforce by 8,500 people over this Parliament is welcome, a bolder and more detailed plan is needed to deliver meaningful change for children and young people.

Despite the major ongoing shortfalls in provision of support, the alarming growth of the crisis in children and young people’s mental health is widely recognised among policymakers and is a significant concern for millions of parents. A survey conducted by the NSPCC in 2024 found that three in four parents with children under five are anxious about their child’s emotional and mental wellbeing (Deloitte, 2024). Recent polling conducted by More in Common on behalf of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition further found that 59% of adults believe that political leaders have failed to do enough to address the mental health needs of children and young people in the last decade (CYPMHC, 2024).

One of the major barriers to meaningful action being taken has been contentions about the role of different drivers of the crisis – such as the pandemic, the cost-of-living crisis, social media and failing services. It’s clear that the Government needs to be given the confidence to act on the challenges and failures that have led to this point, and, critically, to shape ongoing approaches to prevention and early intervention.

Local councils play a pivotal role in delivering a range of services that can be beneficial to young people’s mental health, particularly preventative services and those that often interact with CYPMHS, such as special educational needs and disabilities (SEND) services, children and family services, youth services, and public health initiatives.

However, many of these vital services are buckling under growing financial pressures and demand for support. For example, in children’s social care, recent analysis by the Association of Directors of Children’s Services found that mental health has been increasingly cited as a factor within child early help assessments, growing from 9.1% in 2017/18 to 13.6% in 2021/22 (ADCS, 2022). Meanwhile, analysis by Pro Bono Economics, commissioned by the Children’s Charities Coalition in 2024, revealed that councils in England are now spending more on social care for children and families than ever before (Larkham, 2024). In 2022-23 alone, spending increased by over £600 million – a 5% rise compared to the previous year – bringing total annual expenditure to more than £12.2 billion.

The SEND system for children and young people is nearing breaking point. A January 2025 parliamentary report by the Public Accounts Committee highlighted that, despite a 58% increase in high needs funding over the past decade, the demand for support has surged dramatically (Public Accounts Committee, 2025). The number of children with Education, Health and Care (EHC) plans – critical for addressing their specific needs – has risen every year since 2015. By 2024, 576,000 children aged 0-25 had an EHC plan, marking a staggering 140% increase since January 2015. The report also identified mental health as one of the three fastest-growing areas of demand within the system (ibid), reflecting the higher prevalence of mental health problems among this group. Young people with special educational needs face a 47% incidence rate of mental ill health compared to 9% for their peers without special needs (Sadler et al., 2017). Reforming and investing in these systems is crucial to ensure that babies, children, and young people with multiple or complex needs receive timely, comprehensive support. Such efforts not only address their immediate needs but also help prevent the need for more costly and intensive interventions in the future.

Increased funding for councils would also enable expanded access to, for example, youth clubs, school nursing, family hubs, social prescribing, health visitors and other outreach programmes. These services can address the root causes of mental ill health, including social isolation or family issues (such as poverty or unmet parental mental health problems), and are a vital part of the measures needed to reduce the burden on mental health services. They can also reach babies and toddlers at a crucial stage of their development, when early intervention is key to preventing mental health conditions.

Moreover, economic evaluations of well-known parenting programmes, such as Incredible Years and Triple P, often funded through councils, demonstrate their effectiveness in addressing childhood mental health problems like conduct disorders (Parsonage et al., 2014). These programmes also generate significant savings for public services. For example, recent analysis found that every £1 spent on parenting programmes generates up to £15.80 in the long term (McDaid and Park, 2022).

An Institute for Fiscal Studies evaluation of the Sure Start model, which serves as the foundation for the family hub initiative, also found that these services positively impacted children’s educational achievement, particularly those from lower-income households (Carneiro et al., 2024). Children who lived near Sure Start centres during their first five years scored an average of 0.8 grades higher in their GCSEs. The programme also helped reduce government spending on SEND support, offsetting approximately 8% of these costs. Even more significant are the long-term benefits for children through improved attainment, leading to higher lifetime earnings. It is estimated that for every £1 the government invested in Sure Start, attending children gained benefits equivalent to £1.09, based solely on improved school outcomes.

The Sure Start programme laid the groundwork for the Start for Life initiative, which launched in 2023 and committed to establishing Family Hubs in 75 council areas (Department of Health and Social Care and Department of Education, 2023). These hubs aim to provide a comprehensive range of support for parents, carers, and children, from conception through to age 19 – or up to 25 for those with special educational needs and disabilities. Services include midwifery, health visiting, mental health support, and early help provision. While £82 million was allocated in 2022 to fund the programme until Spring 2025 (Department for Education, 2022), early evaluations indicate promising outcomes (Department for Education, 2023).

Despite this progress, the programme’s long-term future remains uncertain, including funding for nationwide implementation. This is concerning, given that the Government’s own guidance estimates that 10% of babies are living in fear and distress, putting them at risk of ‘disorganised attachment’ and wider negative outcomes (HM Government, 2022).

Returning local government spending on youth services to 2015-16 levels, in real terms, would mean a total annual spend of over £750 million at present (calculated as over £640 million in 2022-23) (YMCA, 2024). This investment in prevention and early intervention could save further billions in avoided costs. In 2022, Frontier Economics estimated savings of up to £3.2 billion to be gained from investment in youth services (approximately £3.8 billion in real terms now) (Frontier Economics, 2022).

Councils have called for the funding of the now closing National Citizen Service (NCS) to be reallocated to youth services (Local Government Association, 2024a); funds that could be reallocated stand at £52.1 million (excluding £2.1 million that NCS planned to self-generate) (UK Government & Skills for Life, 2017). Such a funding diversion would be welcome, but with an estimated increase of £314 million annually needed to return funding of youth services to 2015-16 levels, this would only go part of the way.

The Health Foundation has outlined multiple budgeted options for restoring the Public Health Grant to 2015/16 real-terms levels, including options to address geographical inequalities in grant allocation (Patel et al., 2024). The most basic restoration plan would require an increase of £1.4 billion per year or a phased approach over five years totalling £4.6 billion in additional spend.

The minimum £2.6 billion (Franklin et al., 2023) required to deliver the children’s social care reform proposed in the Macalister Review (2022) must now be adjusted for inflation and the cost incurred by delays to reform, meaning the necessary figure will now likely exceed £3 billion. The Children’s Social Care Prevention Grant is worth £263 million (Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, McMahon & Rayner, 2024) (uplifted from £250 million in the Autumn Budget announcement [Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government, 2024]). This brings direct Local Government Finance Settlement investment into preventative children’s social care to over half a billion for 2025/26.

Based on figures as of June 2024, councils forecast a collective shortfall of £926 million between SEND support need and funding for the year, based on increasing Education, Health and Care Plans (EHCPs) in 2023 (rising by 26.6% compared to 2022) (Winson, 2024). The Government has announced an intended £1 billion increase to SEND and Alternative Provision funding (Children’s Commissioner, 2024b), but without continued commitment to increased funding this will not meet forecast levels of need (and numbers of ECHPs), which would create a cumulative local authority deficit of over £8 billion by 2027 (Sibieta & Snape, 2024).

Reforming the current SEND system, which has been identified as ‘not fit for purpose’, will also come with costs (Lepper, 2024). This is supported by evidence that increasing spending has not sufficiently improved educational attainment amongst children with SEND, despite council spending on SEND services projected to be £12 billion by 2026, compared to £4 billion in 2015 (Isos Partnership, 2024).

Councils will also have to factor in recently announced National Insurance increases, requiring an additional £637 million for directly employed staff and £1.13 billion for external providers (Local Government Association, 2024b).

It is clear that investing in children’s mental health is not only a moral imperative but also an economic necessity. The current crisis is a ticking time bomb, with far-reaching consequences for children and young people, families, and the nation. By addressing this challenge now, the Government has a critical opportunity to secure a healthier, more prosperous future for young people and society as a whole. The evidence is undeniable: investing in high-quality prevention, early intervention, and accessible services can reverse current trends, reduce long-term costs, and unlock the potential of an entire generation.

Bold leadership and systemic reform are essential to scale up proven interventions, alleviate the strain on public services, and foster economic resilience. Failure to act risks perpetuating cycles of inequality, increasing economic burdens, and leaving millions of young people unable to achieve their full potential. We must see investing in children’s mental health as an investment in the future of our society – a future we cannot afford to jeopardise.

"My name is ZeZe and I am autistic and have schizophrenia. I experienced emotion dysregulation as part of my autism. When I was 11, I started self-harming due to trauma at home. I went on medication for my mental health when I was 11 but continued to deteriorate. I became suicidal at 13 and ended up in an inpatient unit at 14. I was suicidal and psychotic at this point – I thought snipers were out to get me, I wouldn’t eat because I was paranoid that people were poisoning me, wouldn’t take medication for the same reason, and I wouldn’t sleep for six days at a time because I thought people would hurt me in my sleep. I was very unwell. At one point I was observed by three people 24/7 because I was suicidal. I was restrained for 1.5 hours at a time.

However, when I went to a low secure unit, the team didn’t see a young person who was severely unwell; they saw me as a young person with great potential to succeed. They slowly gained my trust over six months and they offered me long-term therapy which I engaged in. I had a named mental health nurse who collaborated with me in my care in a hope-based way and gave me a consistent approach to my distress. He worked with me on my goals to get better and do my GCSEs, and he would always show up to build my trust. He worked with me rather than doing things to me. It was life saving and life changing, I wouldn’t be where I am without this support.

Now I am chief exec of my own charity that supports autistic young people in inpatient units. I am a multi-award-winning mental health advocate. I have a Churchill Fellowship to research care leavers with psychosis. I have spoken at the United Nations. Most importantly, I have built a life worth living which wouldn’t have happened without the vital support of mental health services.

In the face of a major and growing crisis in children and young people’s mental health, four of the UK’s leading children and young people’s and mental health organisations – Centre for Mental Health, the Centre for Young Lives, the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition and YoungMinds, with the support of the Prudence Trust – have joined forces to call on the Government to deliver urgent reform and investment, ahead of the major long-term policy decisions that will be taken in the forthcoming Spending Review and 10 Year Plan for Health in England.

Contact: Adam Jones, Future Minds Campaign Lead

adam.jones@youngminds.org.uk

The lead authors of this report were Adam Jones and Kadra Abdinasir.

We thank all the members of the Future Minds Campaign who contributed to this report, in particular: Julia Doyle, Alethea Joshi, Andy Bell, Charlotte Rainer, Baroness Anne Longfield, Connie Muttock, Jo Green, Tara Leathers, Karis Eaglestone, Laura Bunt, Olly Parker, Ellie White and Elise Neve.

Association of Directors of Children’s Services (2022) Safeguarding pressures phase 8. Special thematic report on children’s mental health. Available at: https://www.adcs.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/04/ADCS_Special_Thematic_Report_on_Mental_Health.pdf

Balmer, J.N., Pleasence, P (2012) The Legal Problems and Mental Health Needs of Youth Advice Service Users: The Case for Advice. Youth Access. Available at: https://cdn.baringfoundation.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2014/09/YAdviceMHealth.pdf

Barnardo’s (2022) It’s hard to talk. Expanding Mental Health Support Teams in Education. Available at: https://www.barnardos.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-01/hardtotalk-expandingmentalhealthsupportteamsschools-MHSTs-report-jan2022-v2.pdf

Carneiro, P., Cattan, S., & Ridpath, N (2024) The short- and medium-term impacts of Sure Start on educational outcomes. Institute for Fiscal Studies. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/sites/default/files/2024-04/SS_NPD_Report.pdf

Cardoso, F. and McHayle, Z. (2024) The economic and social costs of mental ill health. London: Centre for Mental Health. Available at: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/the-economic-and-social-costs-of-mental-ill-health/

Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition (2024) Shaping tomorrow: Prioritising babies’, children’s and young people’s mental health in the 2024 election. Available at: https://cypmhc.org.uk/publications/shaping-tomorrow-prioritising-babies-childrens-and-youngpeoples-mental-health-in-the-2024-election/

Children’s Commissioner (2024) Children’s mental health services 2022-23. Available at: https://assets.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/wpuploads/2024/03/Childrens-mental-health-services-22-23_CCo-final-report.pdf

Children’s Commissioner (2024b) Budget 2024: Children’s Commissioner’s reaction. Available at: https://www.childrenscommissioner.gov.uk/blog/budget-2024-childrens-commissioners-reaction/#:~:text=Among%20the%20announcements%20was%20that,system%20was%20financially%20’unsustainable’.

Clarke H, Morris W, Catanzano M, Bennett S, Coughtrey AE, Heyman I, Liang H, Shafran R, Batura N. Cost-effectiveness of a mental health drop-in centre for young people with long-term physical conditions. BMC Health Serv Res. 2022 Apr 19;22(1):518. doi: 10.1186/s12913-022-07901-x. PMID: 35440005; PMCID: PMC9016208.

Darzi, A (2024) Independent investigation of the NHS in England. Department of Health and Social Care. Available from: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/66f42ae630536cb92748271f/Lord-Darzi-Independent-Investigation-of-the-National-Health-Service-in-England-Updated-25-September.pdf

Deloitte (2024) Poor mental health costs UK employers £51 billion a year for employees. Available at: https://www.deloitte.com/uk/en/about/press-room/poor-mental-health-costs-ukemployers-51-billion-a-year-for-employees.html

Department for Education (2022) Press release: Infants, children and families to benefit from boost in support. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/infants-children-and-families-to-benefit-from-boost-in-support

Department for Education (2023) Family Hubs Innovation Fund Evaluation Final research report. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6567764dcc1ec5000d8eef10/Family_Hubs_Innovation_Fund_Evaluation_Ecorys_Final_Report.pdf

Department for Education (2024) Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Implementation Programme. Data release. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/6641f1e1ae748c43d37939a3/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_implementation_programme_2024_data_release.pdf

Department of Health and Social Care (2024) Press release: Extra funding for early support hubs. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/extra-funding-for-early-support-hubs

Department of Health and Social Care (2018) Impact Assessment. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/5b583deded915d0b85eea618/impact-assessment-for-tranforming-cy-mental-health-provision-green-paper.pdf

Department of Health and Social Care and Department for Education (2023) Family Hubs and Start for Life programme. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/collections/family-hubs-and-start-for-life-programme

Early Intervention Foundation (2018). The cost of late intervention: EIF analysis 2016. [online] Early Intervention Foundation. Available at: https://www.eif.org.uk/report/the-cost-of-late-intervention-eif-analysis-2016

Ellins, J., Hocking, L., Al-Haboubi, M., Newbould, J., Fenton, S. J., Daniel, K., … & Mays, N. (2023). Early evaluation of the Children and Young People’s Mental Health Trailblazer programme: a rapid mixed-methods study. Available at: https://www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/hsdr/XQWU4117#fullreport

Ellins, J., Hocking, L., Al-Haboubi, M., Newbould, J., Fenton, S. J., Daniel, K., … & Mays, N. (2024). Implementing mental health support teams in schools and colleges: the perspectives of programme implementers and service providers. Journal of Mental Health, 33(6), 714-720. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37937764/

Franklin, J., Larkham, J., & Mansoor, M (2023) The well-worn path. Available at: https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2023-09/Children%27s%20services%20spending_final%20report_0.pdf

Franklin, J., Prothero, C., & Sykes, N (2024) Charting a happier course for England’s children: the case for universal wellbeing measurement. Available at: https://www.probonoeconomics.com/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=2779dc06-66cd-43c5-9310-94cf0c572104

Frayman, D., Krekel, C., Layard, R., MacLennan, S., & Parkes, I (2024) Value for Money. How to improve wellbeing and reduce misery. London School of Economics. Available at: https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/special/cepsp44.pdf#page=19

Frontier Economics (2022) The economic value of youth work. UK Youth. Available at: https://www.ukyouth.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/Economic-Value-of-Youth-Work-Full-Report.pdf

Garratt, K., Kirk-Wade, E & Long, R (2024) Children and young people’s mental health: policy and services (England). House of Commons Library. Available at: https://commonslibrary.parliament.uk/research-briefings/cbp-7196/#:~:text=This%20represents%208%25%20of%20planned,eating%20disorders%20the%20previous%20year

Goodman, A., Joyce, R., Smith, J.P. (2011) The long shadow cast by childhood physical and mental problems on adult life. PNAS 108:15 6032-37. Available at: https://www.pnas.org/doi/epdf/10.1073/pnas.1016970108

Gutman, L. et al. (2015) Children of the new century. Centre for Mental Health. Available from: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/children-new-century

HEE (2023) Health Education England Children and Young People’s Mental Health Workforce Census. Available at: https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/Children%20and%20Young%20People%27s%20Mental%20Health%20Workforce%20Census%202022_National%20Report_24.1.23.pdf

HM Government (2024) Get Britian Working. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/67448dd1ece939d55ce92fee/get-britain-working-white-paper.pdf

HM Government (2022) Family hubs and start for life programme guide. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/62f0ef83e90e07142da01845/Family_Hubs_and_Start_for_Life_programme_guide.pdf

ISOS Partnership (2024) Towards an effective and financially sustainable approach to SEND in England. Available at: https://www.countycouncilsnetwork.org.uk/educational-outcomes-for-send-pupils-have-failed-to-improve-over-the-last-decade-despite-costs-of-these-services-trebling-new-independent-report-reveals/

Judge, L & Murphy, L (2024) Under strain. Investigation trends in working age disability and incapacity benefits. Available at: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/app/uploads/2024/06/20-Under-strain.pdf

Kessler, R. C., Berglund, P., Demler, O., Jin, R., Merikangas, K. R., & Walters, E. E. (2005). Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Archives of general psychiatry, 62(6), 593-602. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/15939837/

KPMG (2022) Evaluation of the national headspace programme. Available at: https://www.health.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/2022/10/evaluation-of-the-national-headspace-program.pdf

Larkham, J (2024) Struggling against the tide: Children’s services spending, 2011-2023. Available at: https://www.barnardos.org.uk/research/struggling-against-tide-childrens-services-spending-2011-2023

Lepper, J (2024) Autumn Budget 2024: Council chiefs welcome £1bn SEND funding boost. CYP Now. Available at: https://www.cypnow.co.uk/content/news/autumn-budget-2024-council-chiefs-welcome-1bn-send-funding-boost/

Local Government Association (2024) Youth services ‘under threat’ without government funding – LGA. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/about/news/youth-services-under-threat-without-government-funding-lg

Local Government Association (2024b) Local government finance policy statement – LGA response. Available at: https://www.local.gov.uk/lg-finance-policy-statement

Long, R & Roberts, N (2025) School attendance in England. House of Commons Library. Available at: https://researchbriefings.files.parliament.uk/documents/CBP-9710/CBP-9710.pdf

McAlister, J (2022) Independent review of children’s social care: final report. Department for Education. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/independent-review-of-childrens-social-care-final-report

McCurdy, C. & Murphy, L. (2024) We’ve only just begun. Action to improve young people’s mental health, education and employment. Available at: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/weve-only-just-begun/

McDaid, D. and Park, A. (2022) The economic case for investing in the prevention of mental health conditions in the UK. London: Mental Health Foundation. Available at: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-06/MHF-Investing-in-Prevention-Full-Report.pdf

McGorry, P. D., Mei, C., Dalal, N., Alvarez-Jimenez, M., Blakemore, S. J., Browne, V., … & Killackey, E. (2024). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission on youth mental health. The Lancet Psychiatry, 11(9), 731-774. Available at: https://www.thelancet.com/article/S2215-0366(24)00163-9/abstract

M&S and YoungMinds (2023) Understanding young people’s mental health in 2023: A report by M&S and YoungMinds. Available at: https://corporate.marksandspencer.com/sites/marksandspencer/files/2023-10/YoungMinds%20Draft%20Report%20Final.pdf

Mental Health Australia and KPMG (2018) Investing to save. The Economic Benefits for Australia of Investment in Mental Health Reform. Available at: https://mhaustralia.org/sites/default/files/docs/investing_to_save_may_2018_-_kpmg_mental_health_australia.pdf#page=10

Mental Health Foundation (n.d) Investment into mental health research: statistics. Available from: https://www.mentalhealth.org.uk/explore-mental-health/mental-health-statistics/investment-mental-health-research-statistics

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government (2024) Local government finance policy statement 2025 to 2026. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/local-government-finance-policy-statement-2025-to-2026/local-government-finance-policy-statement-2025-to-2026

Ministry of Housing, Communities & Local Government., McMahon, J., Rayner, A (2024) £69 billion to support councils and help deliver Plan for Change. Available at: https://www.gov.uk/government/news/69-billion-to-support-councils-and-help-deliver-plan-for-change#:~:text=Minister%20of%20State%20for%20Local,thrown%20into%20a%20broken%20system

Murphy, L. (2024) A U-shaped legacy. Taking stock of trends in economic inactivity in 2024. Resolution Foundation. Available at: https://www.resolutionfoundation.org/publications/a-u-shaped-legacy/

National Children’s Bureau (2022) More children at risk as councils forced to halve spending on early support. Available from: https://www.ncb.org.uk/about-us/media-centre/news-opinion/more-children-risk-councils-forced-halve-spending-early-support

NHS England (2023) NHS Long Term Workforce Plan. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-long-term-workforce-plan/

NHS England (n.d) NHS mental health dashboard. Available at: https://www.england.nhs.uk/mental-health/taskforce/imp/mh-dashboard/

NHS England (2019) The NHS Long Term Plan. Available at: https://www.longtermplan.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/nhs-long-term-plan-version-1.2.pdf#page=50

NHS Digital (2023) Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2023 – wave 4 follow up to the 2017 survey. Available at: https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2023-wave-4-follow-up

Northover, G. (2021). Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services GIRFT Programme National Specialty Report. [online] Available at: https://gettingitrightfirsttime.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/CYP-Mental-Health-National-Report-22-11h-FINAL.pdf [Accessed 28 Jan. 2025].

O’Keeffe, L., O’Reilly, A., O’Brien, G., Buckley, R. and Illback, R., 2015. Description and outcome evaluation of Jigsaw: an emergent Irish mental health early intervention programme for young people. Irish Journal of Psychological Medicine, 32(1), pp.71-77.

Patel, N., Gazzillo, A., Vriend, M., Finch, D., & Briggs, A (2024) Options for restoring the public health grant. The Health Foundation. Available at: https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/briefings/options-for-restoring-the-public-health-grant#:~:text=In%202024%2F25%2C%20the%20total,2.9%25%20in%202013%2F14

Parsonage, M., Khan, L. & Saunders, A., (2014). Building a better future: the lifetime costs of childhood behavioural problems and the benefits of early intervention. Available from: https://www.centreformentalhealth.org.uk/publications/building-better-future/

Pitchforth, P., Fahy, K., Ford, T., Wolpert, Viner, R. M., Hargreaves, D. S. (2018), Mental health and well-being trends among children and young people in the UK, 1995–2014: analysis of repeated cross-sectional national health surveys. Psychological Medicine 49(8):1275-1285. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/psychological-medicine/article/mental-health-and-wellbeing-trends-among-children-and-young-people-in-the-uk-19952014-analysis-of-repeated-crosssectional-national-health-surveys/AB71DE760C0027EDC5F5CF0AF507FD1B

Pro Bono Economics (2020a) Assessment of the long-term societal benefits from Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Available at: https://www.probonoeconomics.com/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=1a2e6cb9-14b4-46ba-ad69-b4109a64ad08

ProBono Economics (2020b) The impact of waiting lists for children’s mental health services on the costs of wider public services. Available at: https://www.probonoeconomics.com/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=5e8a0aad-e717-4318-baba-56796b9e9e6b#page=9

Pro Bono Economics (2022) Stopping the spiral. Children and young people’s services spending 2010-11 to 2020-21. Available at: https://www.probonoeconomics.com/Handlers/Download.ashx?IDMF=1514961c-7bcd-4b59-84c4-0eed9ec32adf

Public Accounts Committee (2025) Support for children and young people with special educational needs. House of Commons. Available from: https://committees.parliament.uk/publications/46238/documents/231788/default/

Public First (2024) The Case for Counselling in Schools and College. A socioeconomic impact assessment. Available at: https://www.publicfirst.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/School-counselling-report-1.pdf

Rainer, C. and Abdinasir, K. (2023) Children and young people’s mental health: An independent review into policy success and challenges over the last decade. London: Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition. Available from: <https://cypmhc.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/ Review-of-CYP-Mental-Health-Policy-Final-Report.-2023.pdf>

Reardon, T., Harvey, K. and Creswell, C., 2020. Seeking and accessing professional support for child anxiety in a community sample. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 29(5), pp.649-664.

Sadler, K., Vizard, T., Ford, T., Goodman, A., Goodman, R. and McManus, S., 2018. Mental health of children and young people in England, 2017: trends and characteristics.

Sibieta, L (2021) The crisis in lost learning calls for a massive national policy response. Institute for Fiscal Studies. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/articles/crisis-lost-learning-calls-massive-national-policy-response

Sibieta, L & Snape, D (2024) Spending on special educational needs in England: something has to change. Institute of Fiscal Studies. Available at: https://ifs.org.uk/publications/spending-special-educational-needs-england-something-has-change

UCL (2024) MHPRU-2 Projects. Available at: https://www.ucl.ac.uk/psychiatry/research/nihr-mental-health-policy-research-unit/mhpru-2-projects

UCL Institute of Education, Institute for Fiscal Studies & Rand Corporation (2015) Counting the true cost of childhood psychological problems in adult life. Available at: https://cls.ucl.ac.uk/counting-the-true-cost-of-childhood-psychological-problems-in-adult-life/#:~:text=At%2023%20they%20earn%2020,a%20third%20less%20(30%25)

UK Government (2024) Opposition policy costing- Mental Health Support Workers- Labour. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/664716b2b7249a4c6e9d36c7/20240129_Opposition_Costing_-_Mental_Health_Workers.pdf

UK Government & Skills for Life (2017) National Citizen Service Trust. Annual Business Plan 2024/25. Available at: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/665069c7c86b0c383ef64f72/NCS_Trust_Annual_Business_Plan_WEB.pdf

UK Parliament (2024) Children’s Mental Health Week debate. Hansard. Available at: https://hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/2024-01-30/debates/5C6403AD-7A0D-4A3C-945B-E634BF47C9AF/Children%E2%80%99SMentalHealthWeek2024#contribution-3BC198E8-A4A0-48A9-8D8E-82735D0F2088

Winson, L (2024) Councils face deficit of almost £1bn in funds needed to support children with SEN: report. Local Government Lawyer. Available at: https://www.localgovernmentlawyer.co.uk/education-law/394-education-news/57713-councils-face-deficit-of-almost-1bn-in-funds-needed-to-support-children-with-sen-report

YMCA (2024) On the Ropes. The impact of local authority cuts to youth services over the past 12 years. Available at: https://ymca.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2024/06/ymca-on-the-ropes-report-A4.pdf

Youth Access (2021) The case beyond Covid: Evidence for the role of Youth Information Advice and Counselling Services in responding to young people’s needs in the pandemic and beyond. Available at: https://www.youthaccess.org.uk/sites/default/files/uploads/files/the-case-beyond-covid.-evidence-briefing.-online_0.pdf

Youth Access (nd) The Youth Access Model. Available at: https://www.youthaccess.org.uk/our-work/championing-our-network/youth-access-model

Where figures have been adjusted for inflation, these calculations have been based on historic and current UK CPIH inflation data published by ONS. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/economy/inflationandpriceindices/datasets/consumerpriceinflation

Estimating the total cost of lifetime earnings loss for individuals affected by mental health difficulties in childhood considered how to begin updating the figure of £550 billion produced by UCL Institute of Education, the Institute for Fiscal Studies and RAND Corporation in 2015.

Raising the estimate of households affected from 6.8% to 13.5% is an approximation of increased rates of mental health difficulties and reflects a broader understanding of these difficulties than that applied during data collection for older studies. These studies relied on data on whether children had seen a psychologist or psychiatrist, a diagnosis of psychological conditions or a doctor ‘detect[ing…] emotional maladjustment’ (Goodman, Joyce and Smith, 2011). In contrast, data collection like the NHS Mental Health of Children and Young People in England Survey aims to reflect the prevalence of mental health difficulties where barriers to support and diagnosis could be skewing previous counts. In that survey, between 2017 and 2023, rates of probable mental health disorders increased from 12.5% to 20.3% in 8-16 year olds and from 10.1% to 23.3% in 17-19 year olds (NHS Digital, 2023).

Research has found that between 1995 and 2014 alone, the percentage of 4–24-yearolds reporting a mental health condition rose from 0.8% to 4.8% in England (Pitchforth et al., 2018). The previous datasets pertain to individuals who would have been children and young people in the 1960s or 1970s and the 1980s and 1990s, respectively and so a new estimation should more closely reflect changes in children and young people’s mental health data since then.